Stolon Studio Director, Robert Barker, was asked by the Architects' Journal to comment regarding our experience of TfL sites. In this article, Robert highlights the challenges facing both designers, developers and the TfL managers. He also supposes that these challenges may contribute to the reasons why some schemes have met such resistance.

"Undoubtedly, there is a need to provide new homes and there is pressure for TfL to generate funds from disposing of sites for development. But I believe that the measure of success on these sites are not these two factors alone – i.e. not the income generated for TfL and not the number of new homes."

‘There is always a need for balancing development and design. As I understand, TfL are required by the GLA Act 1999 to maximise income from any disposal of its sites. I also understand that through the London Plan, TfL are to provide 50% affordable housing on all major schemes (as it is public land). In contrast, on private land, the requirement is to deliver 35% affordable housing (through the fast track). This indicates that TfL are obliged to maximise the economic value of any given site and ensure that they can maximise the number of affordable homes. Whilst this may sound reasonable, it is likely to put pressure on development teams to be overly optimistic at planning stages. If they were not to be ambitious, the proposals would conflict with TfL obligations of maximising the economic value of a site.

There is nothing wrong with seeking to optimise a site’s potential, as long as it is not done in isolation. One needs to balance and consider all aspects of the site: constraints, context, orientation, sustainability, privacy, amenity etc. In the TfL document ‘Design Principles For TfL Development Partners, 2017’ it makes many references to qualitive aspects of design that should be achieved, such as:

- Being well-integrated into their surroundings

- Having a positive environmental impact

- Being aesthetically sensitive

- Providing active frontages

- Improving the sense of place etc

However, it does not appear to mention the obligation to maximise commercial value or the number of homes. Perhaps it is not just the best financial offer but a scheme that appears to offer quantity as well as quality would be hard to turn down over one that might offer quality as well as (maybe a bit less) quantity. Does this approach lead to the most appropriate design for a site, benefit to the public realm, or the one that provides the most value (not just commercial) to Londoners?

In a competition for Greenwich Council, we told them that their brief was too ambitions, and they would not secure planning consent. They understood, and awarded us the project, but even then, we worked hard to justify the scheme at planning. It is just starting on site now.

Many of the bigger TfL sites are in significant public locations, ie close to transport links. This provides good levels of accessibility that invariably supports the principle of high-density, high-performance housing. However, it means that these sites may also have a role to play in providing other uses that would benefit from being in such locations and would benefit users of these transport nodes.

I wrote to the GLA (in 2017) raising my concern that the Small Sites Policy[1] proposed in the draft London Plan was solely for housing, when many small sites could provide other uses that help to support communities and local businesses. This seems even more important now that more people are working from home and that the workforce is more widely distributed. This presumably also applies to TfL, such that their allocation of sites for housing can be more nuanced with other uses to create genuine mixed-use development. TfL could be well placed to support a variety of uses and innovation, though I appreciate that this may not generate the (much needed) capital receipts that would be achieved through the disposal of sites.

As TfL looks to expand its programme, there needs to be an opportunity for moments of reflection, to review what it delivers to see how closely these meet the design standards it has set itself, and to ensure that greater emphasis is given to place-making, and environmental and social value. Buildings take years to design and deliver, just moments to get wrong, and last for generations living with the consequences.

Perhaps the emphasis of TfL developments, and the GLA act, needs to be updated to encompass a wider recognition of the term Value so that it places greater emphasis on the social and environmental value of development, not just the economic.

We have partnered with development companies on both build-to-sell and build-to-rent schemes. One of the interesting aspects of the build-to-rent model is that the developer retains responsibility for the success of the development, long after it is completed. The maintenance, management and up-keep is key to the whole community well-being, and desirability of a place. Developer turns investor. This means that longevity, environmental performance and social value all take greater priority to the investor than they might do otherwise. This can often lead clients to take a cautious approach to design and innovation, but in our experience design and planning, innovation can offer significant benefits for clients and occupants, willing to embrace new thinking. The recent lockdowns have given us great insight into the successes and future opportunities of our residential and mixed-use schemes and we strongly believe that these could become more mainstream for the enlightened developer.

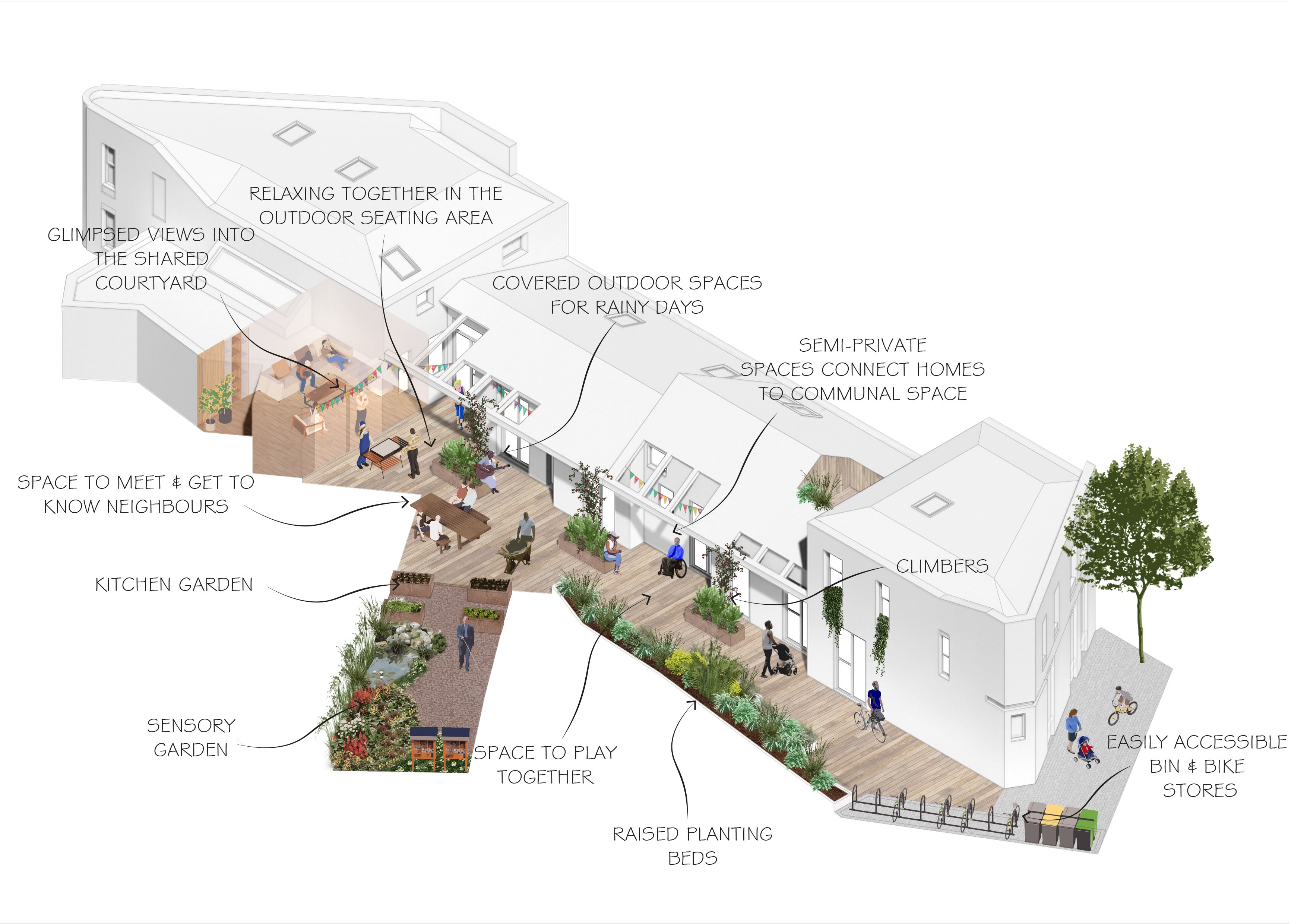

In our own work we are seeking to create high-quality spaces in and between buildings that encourage social interaction, access to the outdoors and access to the natural environment, all with known health and well-being benefits. These have the benefit of supporting high-density places that people can thrive in and that have an environmental bias both in-terms of carbon reduction and the relationship with the environment within which they sit – key aspects of tackling the climate crisis.

As TfL seeks to expand its housing programme, we hope that they embrace new more environmental and sociable housing models and that this will have long-term commercial benefits for the publicly owned organisation and social benefits to the immediate and wider community.’

[1] This was after some research work, we had been doing into a concept for micros2macro. This is the idea of taking the requirements for a major development site and distributing them across several small (micro) sites such that they would collectively deliver a vibrant range of needs, including number and mix of homes, accessible units, green space, commercial etc.